- ImpactWe help parliaments to become greener and to implement the Paris agreement.We support democracy by strengthening parliamentsWe work to increase women’s representation in parliament and empower women MPs.We defend the human rights of parliamentarians and help them uphold the rights of all.We help parliaments fight terrorism, cyber warfare and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.We encourage youth participation in parliaments and empower young MPs.We support parliaments in implementing the SDGs with a particular focus on health and climate change.

- ParliamentsNearly every country in the world has some form of parliament. Parliamentary systems fall into two categories: bicameral and unicameral. Out of 190 national parliaments in the world, 78 are bicameral (156 chambers) and 112 are unicameral, making a total of 268 chambers of parliament with some 44,000 members of parliament. IPU membership is made up of 180 national parliaments

Find a national parliament

We help strengthen parliaments to make them more representative and effective. - EventsVirtual eventThe International Court of Justice (ICJ) was constituted under the United Nations Charter to help nations settle disputes peacefully in accordance with international law.

- Knowledge

Discover the IPU's resources

Our library of essential resources for parliamentsGlobal data for and about national parliamentsLatest data and reports about women in parliamentResolutions, declarations and outcomes adopted by IPU MembersRecent innovations in the way parliaments workThe latest climate change legislation from the London School of Economics' database

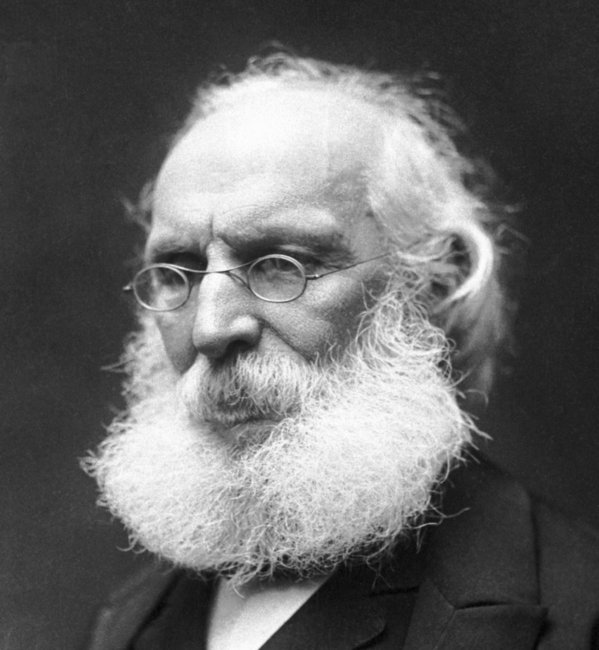

Co-founder Frédéric Passy

The world is made of achieved utopias. Today’s utopia is tomorrow’s reality — Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy dedicated 50 years of his life to promoting arbitration and reconciliation between nations. He became known as the “Apostle of Peace”, winning the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 alongside Henri Dunant, the founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Passy was born into the French establishment in Paris on 20 May 1822. His father was a veteran of Waterloo while his uncle, Hippolyte Passy, was a cabinet minister under both Louis Philippe and Louis Napoleon.

Passy was educated as a lawyer, before joining the civil service as an accountant at 22 years of age. But he came under his uncle’s influence and left after three years to devote himself to studying economics, becoming a renowned scholar with a reputation as a skilful speaker.

Passy’s interest in peace began with the Crimean War (1853–56). In the closing stages of the conflict the Loire river in France flooded, causing widespread damage. It struck Passy that people struggled to absorb the horror of natural disasters, while coming to accept man-made disasters such as war as normal.

Later, as war loomed between France and Germany over the sovereignty of Luxembourg in 1867, Passy wrote an influential plea for peace in the French newspaper Le Temps and called for an international peace society to help avert conflict.

Encouraged by public support, he set up the Ligue International et Permanente de la Paix (International and Permanent League of Peace) to prevent conflicts in the future. The League failed to prevent the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 and was dissolved. Not to be discouraged, Passy set up the “Société française des amis de la paix” which became more specifically the “Société française pour l’arbitrage entre nations” in 1889.

Passy, a Republican, refused to be a part of government under Napoleon III. He was eventually elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1881 and 1885. While in parliament he supported labour reform, in particular legislation on industrial accidents. He was also opposed to the government’s colonial policy.

As well as drafting a proposal for disarmament, he put forward a motion to debate arbitration of international disputes in 1887. At around the same time, an English MP, William Randal Cremer, had persuaded 234 of his fellow parliamentarians to sign a document proposing an arbitration treaty with the United States.

Cremer became aware of Passy’s activities and suggested a meeting in Paris between English and French MPs to discuss how they could advance arbitration. The meeting went ahead in October 1888, attended by nine English and 25 French parliamentarians. Although not large, it was enough to sow the seeds for a second event the following year which was attended by 83 French and English MPs, as well as 11 MPs from 7 other countries. On 30 June 1889, the meeting was formalized and the Inter-Parliamentary Conference was established with Passy as President.

Passy continued to develop the IPU as an organization committed to the use of arbitration as a means to end conflicts over politics or trade.

In 1901 he was awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his long commitment to international peace, which by then had stretched over some five decades.

Despite his advancing years and failing eyesight, Passy continued his work and his writing, and in 1909 he published Pour la Paix (For Peace) chronicling his work for international harmony. A distinguished and much decorated member of French society, Passy died in Paris on 12 June 1912, aged 90.

Frédéric Passy, born into an influential French family, became a devoted campaigner for peace.